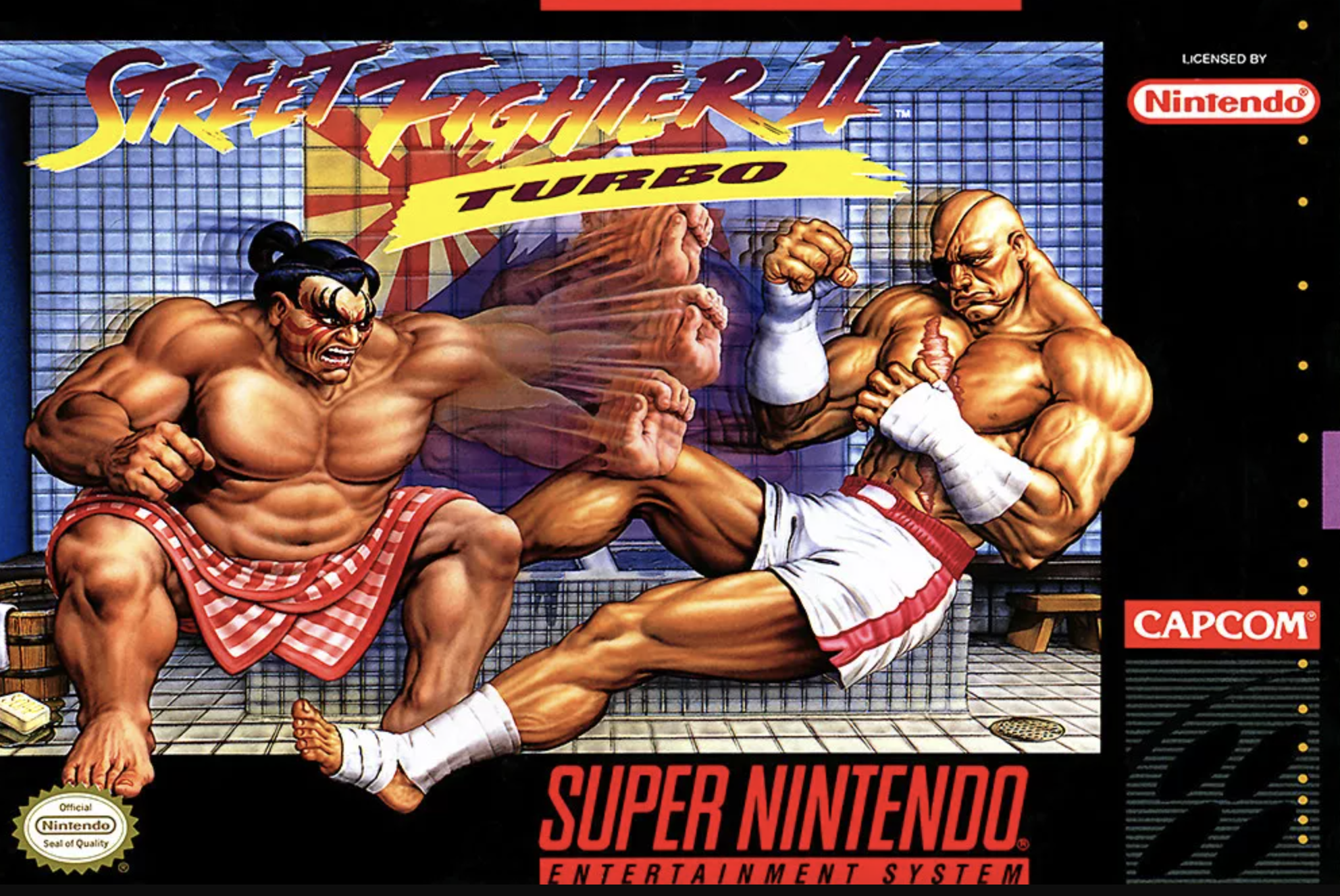

My first exposure to Japanese culture was Street Fighter 2: Turbo on the SNES.

I was six years old. I remember reading the manual on the way home from

buying the game, trying to memorise the special moves. Hand-eye

coordination is still a work in progress when you're six, so it took

tremendous effort to learn how to execute a fireball. Even more so for a dragon

punch. And it would be decades before I could accurately pronounce the word

A few years later came Final Fantasy VII.

FF7 had a lot going for it. The graphics were exemplary for the time, and after the first disc, the world opened up in an unexpected and breathtaking way. It had a strong narrative where you actually cared about the characters, and lots of things to do and see in the world.

I remember procrastinating on beating the final boss in the Northern Crater because I didn't want the experience to end. I'd fly around the world on the Highwind, check in with people in various towns, fight familiar enemies. I probably spent an entire year just pottering around the game world before I finally brought myself to finish it.

When I finally completed it, I remember staring at the screen and immediately regretting my decision. I knew I could reload my save and keep pottering, but there was a sense of finality that meant it would never be quite the same.

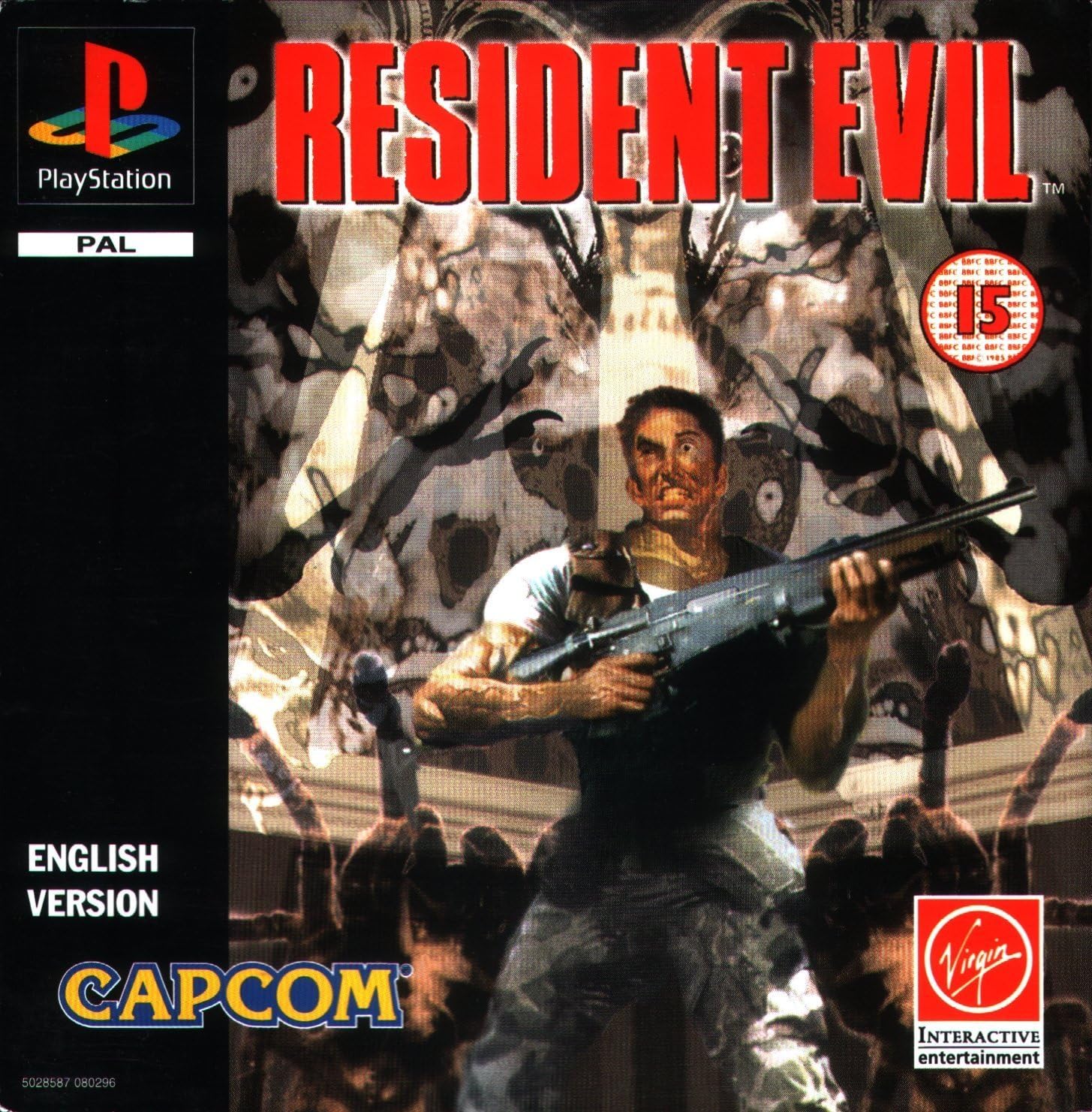

The next big game for me was Resident Evil.

Resident Evil was absolutely fucking terrifying. It had you wandering around a zombie-infested mansion with an arsenal that grew painfully slowly, dwindling supplies, and aggressive, surprising enemies jumping out of every corner. There were other "survival horror" games at the time, but this is the one that really established the genre. Around that time we also had Silent Hill and Onimusha (samurai Resident Evil) which were also great fun.

The next genre-establishing Japanese game I spent a lot of time with was Metal Gear Solid.

Stealth games—or at least stealth as a mechanic—would become ubiquitous in games, but MGS is where I think it all started. It was packed with memorable action scenes and unforgettable characters. Revolver Ocelot and that cyborg ninja would appear at the worst possible moments. And there was a Japanese self-aware zaniness that characterised a lot of Japanese media at the time.

The red exclamation mark appearing above people's heads with the accompanying sound effect is still a recognizable meme on Japanese television.

There were other Japanese games that left a lasting impression on me, but these were the "big three" so to speak.

I was a teen in the 90s, the time of Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Movies were full of stylistic violence and gore.

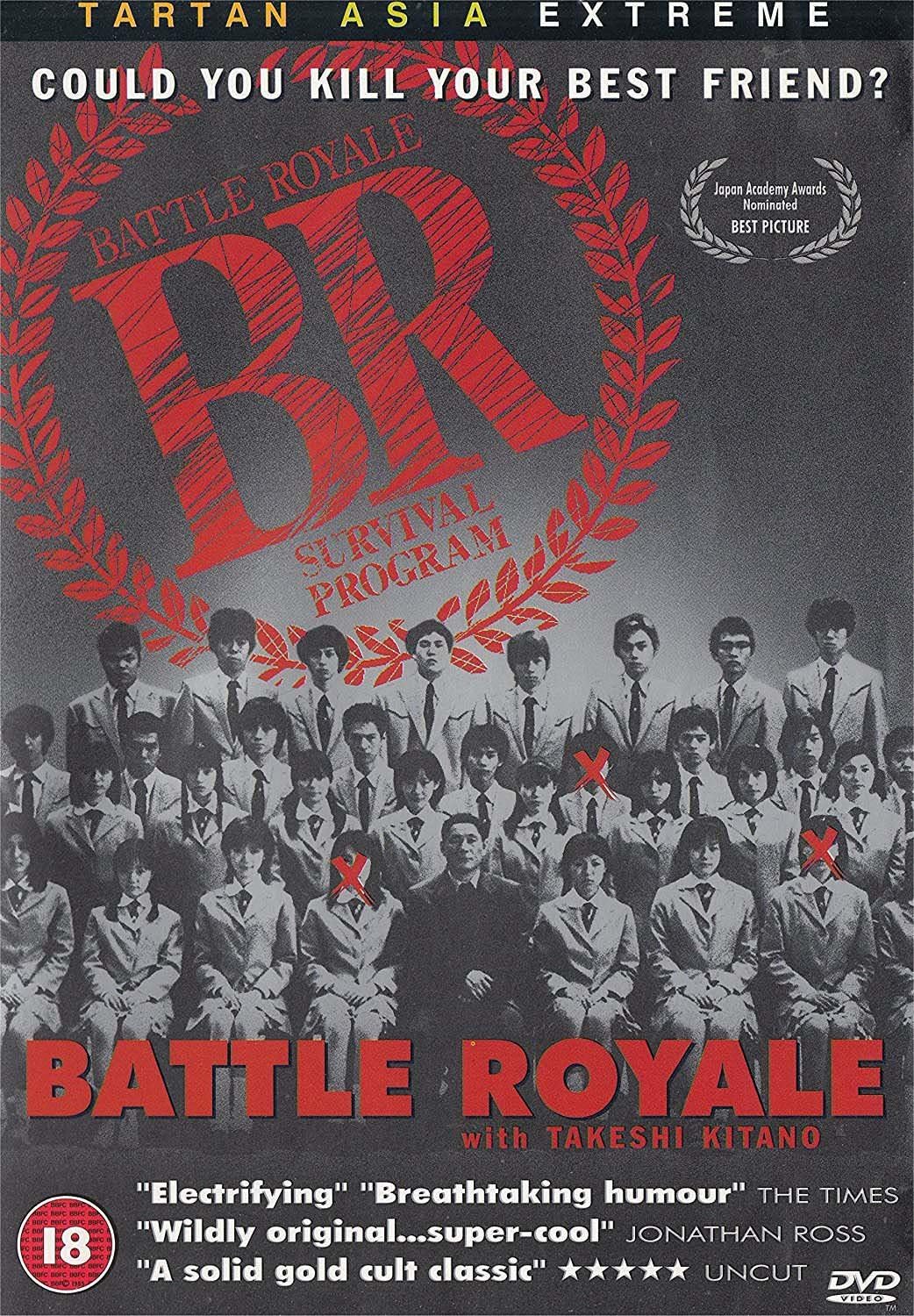

The first Japanese film I watched from beginning to end was Battle Royale.

BR was and still is a very watchable movie. The characters are compelling, the story made sense+. I didn't understand the significance of Beat Takeshi at the time, but many of the cast would go on to become Japanese household names.

+:To me at least, understanding the story is a bit of a luxury in Japanese media. To this day I have absolutely no idea what the fuck is going on in Ghost in the Shell or Princess Mononoke.

Battle Royale was, I think, one of the first places where I heard the spoken Japanese language. Watching BR is probably one of the reasons I would eventually take an interest in learning Japanese, leading to many of the adventures I got into since then.

There was also a sense of secretly watching movies your parents probably wouldn't be happy about you seeing. Japanese culture was still exotic back then, not many people were into it like they are now. I'd saved up my own money to buy the Battle Royale DVD and no one I knew had ever heard of it.

In the same order, I also bought the DVD for Audition.

This was the most harrowing cinematic experience of my life. For most of its runtime, it's a rather boring story of a middle-aged man trying to find love. By the end of the film I was staring at the screen bewildered, thinking What the fuck did I just watch?.

I tracked down many more movies from these two directors, Beat Takeshi and Miike Takashi. I remember I watched City of Lost Souls, Sonatine, and Dead or Alive, which were all good fun. Miike is more of a cult figure in Japan, but was wildly successful outside of Japan at the time.

I also went through a Kurosawa Akira phase, and tried to enjoy classics like Seven Samurai and Rashomon. I liked the back and forth that Kurosawa had with western theatre and cinema. Throne of Blood was basically "Samurai Macbeth", and Seven Samurai would ultimately be reimagined as The Magnificent Seven, A Bug's Life, and an episode of The Mandalorian.

I also tried to enjoy anime like Akira, Ghost in the Shell, and anything by Studio Ghibli, but none of this really resonated with me like games, cinema, and books did.

Japanese literature and books about Japan are what locked in my interest in Japanese culture. Though it wasn't actually a book by a Japanese person that started it. It was James Clavell's Shogun.

Shogun is a dramatised re-telling of the story of Will Adams, an English privateer turned retainer to Tokugawa Ieyasu leading up to the battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

It's grand adventure, pure and simple. The protagonist goes from washing up in a shipwreck on the shores of Japan, to learning every aspect of Japanese culture the hard way, to battling samurais and ninjas, and fooling around with Japanese princesses and courtesans.

I think on some level, I wanted to be like John Blackthorne. To be a dumb foreigner getting into silly adventures in Japan, misunderstanding things and learning, meeting interesting characters, going to strange and exotic places, messing around with strange and exotic women.

It's a long book, and as a moody teenager I spent countless hours with it. I would curl up and play Nara by E.S. Posthumous on repeat, reading for four or five hours at a stretch.

Shogun was originally published in 1975. It was made into a series in 1980 starring Richard Chamberlain. More recently it was made into an Emmy award-winning TV series starring Sanada Hiroyuki and Cosmo Jarvis.

I also read everything by Murakami Haruki. His "genre" can best be described as magically-surrealist bummer fiction. Crazy and incredible things happen in his magical worlds while bumming you out for hours on end. They were highly readable and make excellent conversation fodder with Japanese people, but I can't say I would revisit them.

It was around the time I read Shogun and was watching Kurosawa movies that I got the idea into my head to learn Kendo.

I was around 16 at the time, living in Hounslow, and we had the internet, so I found Mumeishi Kendo Club, and began training under Terry Holt (7dan). With Terry's support and blessing this would eventually lead to me starting UCL Kendo Club.

I'd never done any sports before, and so I was never particularly good at Kendo. I had a few nice moments in competition though, the highlight of which was winning the fighting spirit award at the UK National Taikai for a lucky kote-men, followed by a lucky de-gote against a 5dan.

Kendo got me deeper into Japanese samurai and martial culture. I read the English translations of Hagakure, The Book of Five Rings, and Eiji Yoshikawa's fictionalized account of the most famous swordsman's life: Musashi.

I also read Sun and Steel by Yukio Mishima, which was pretty abstract and difficult to understand then—and honestly, still is now.

Much later, I took up Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. BJJ is another great example of Japanese culture mixing and mingling with other cultures and finding its way back home.

I was around seventeen when I decided to try learning Japanese. We didn't have Anki or really anything on the internet to help. All I could do was start by practicing hiragana by hand. I practiced the first five characters until I could write them from memory, and taught myself five new characters a day until I could write them all in one sitting.

I learned grammar by reading Barron's Japanese Grammar, which teaches sentence structure in romaji. Much of the advice at the time discouraged learning from romaji sources, but this only applies if you can't separate English language text and Japanese romaji text in your mind. This wasn't a problem for me, so this tiny little book was a great resource.

On some level I just intrinsically liked the sound of Japanese, and learning it has never felt like a chore to me. I focused hard on pronunciation first, because no language is fun if you're not intelligible. And since I knew hiragana, I could transliterate any word I heard in conversation, even if I couldn't understand it. This meant I could look up any unknown words, creating this upward spiral of acquiring more and more language ability through each conversation.

Fast forward a decade or so, and I found myself at 34 and freshly divorced. After the share-house era, I moved to the centre of Sendai close to Iroha Yokocho. Iroha Yokocho are a couple of historic alleys with around a hundred tiny bars and restaurants.

When I say close, I mean that I could stop typing this right now and if I caught the elevator at the right moment, I could be in the alleys with a cold beer in my hand in about 90 seconds. This has its pros and its cons.

I like exploring, and so I made it my mission to visit every venue, get to know the staff, eat all the nice food, drink all the nice drink, and submerge myself in this culture. What I found was extremely rich and interesting. There's a rolling cast of characters that run and frequent these places, a long history, and a sense of community. Six years after moving here I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that I have some part to play in that community.

Every conversation with the staff and customers was an opportunity for me to absorb culture, language, and knowledge. And since I live here, I wasn't just a bystander—I was making friends, making countless social blunders, learning from my mistakes, and overall improving my ability to interact in Japanese social contexts.

To outsiders, Japanese social culture might seem monolithic. But after thousands of interactions, it's clear to me that there's immense variation depending on who you're talking to, their life story, and what their values and expectations are. An experienced office worker and a gaggle of hostesses on their day off are going to be polar opposites to interact with, and I had to learn social skills to interact with all sorts.

And each venue attracts and repels different types of Japanese people, so each becomes it's own social context where the rules and expectations are redefined again. In the same way that some people enjoy Magic: The Gathering or sports statistics, I genuinely revel in the little details of these social contexts.

But all those nights in the yokochos, all that immersion in different social contexts—it came with a cost. The intensity of constantly navigating these interactions, combined with everything else going on in my life, left me feeling pretty raw.

For better and worse, I feel emotions with more intensity for longer than most people I know. After long conversations with ChatGPT, we came to the conclusion that I am hyper sensitive to stimulus, and go through cycles of both intense suffering and joy, grasping for pleasure and trying to avoid pain at every turn.

This, in Buddhist contexts, is called samsara, the neverending cycle of birth, death, suffering, and grasping.

I first got into meditation through Sam Harris's Waking Up app. While his fundamentals course and other material were somewhat enlightening, I got a lot of value from listening to the Alan Watts lectures, which are available in full in the app.

Zen emphasises that nirvana and samsara (or 涅槃 and 生死 in zen terms) are non-dual. They're both sides of the same coin, like yin and yang (陰と陽). So enlightenment is the emotional turmoil of my day-to-day life, and those same troubles are where enlightenment is to be found, I think?

Based on my studies so far, Zen doesn't explicitly emphasise non-duality as much as other schools like Dzogchen, but it does emphasise some specific instances of non-duality like this one.

This is another example of extremely traditional Japanese culture going overseas in the sixties and getting taught to me by a bunch of aging hippies, only for me to find it again right here in Japan, exactly when I needed it.

So here I am, decades after that six-year-old kid struggled to execute a hadouken on the SNES. I never did wash up on Japan's shores and become a legendary foreign samurai. Instead, I became something else—a regular at a handful of tiny bars, someone who can navigate both a hostess club and a Zen temple.

The Japanese culture I found wasn't the one I was looking for as a teenager. It's messier, more human, and infinitely more interesting than anything I could have imagined. It's an ongoing negotiation with this culture that adopted me, or that I adopted, or maybe both.